Survival System

Sarah Hromack on a new proposal for the creative economy that responds to a challenging time.

A recent New York Times headline asked “With Prices Soaring, Can New York Survive as Mecca for the Arts?” before detailing the post-pandemic exodus of New York’s art community. Hyperallergic reported on a recent survey by inveterate writer and arts consultant Paddy Johnson whose data shows that artists are plagued by debt regardless of their career stage. The situation is so bad that New York City’s incoming mayor, Zohran Mamdani, has appointed a rather formidable transition committee on arts and culture to take it on.

The time is ripe for a new form of intervention designed to support artists, arts workers, and others seeking to make their way in the world when the national political climate is outright hostile for the arts.

Enter Artist Corporations or A-Corps, an emerging initiative spearheaded by writer and entrepreneur Yancey Strickler. A-Corps is a “new economic paradigm,” in Strickler’s words, taking the form of a proposed legal structure that combines elements of LLCs, corporations, and nonprofits so that collaborators can collectively benefit from the success of their creative work. Strickler explains the concept further in his April 2025 TED talk.

Strickler clearly has a vested interest in collectivity. He was one of the co-founders of Kickstarter, which launched in 2009 as a way for people to take their creative projects directly to the public for crowdfunding instead of pitching to publishers and other gatekeepers. Metalabel, a venture launched in 2024, allows people to collaborate on releases of projects like records and books while pooling resources and splitting profits using the platform’s Stripe-powered back end. The Dark Forest Collective Anthology, a collection of essays by Strickler and friends about the current state of the internet, was the first release and use case for the platform (I reviewed it for Hyperallergic). I used Metalabel to launch a bootleg MoMA T-shirt that a pal and I designed as a fundraiser for artists affected by the LA fires and found the experience seamless. Metalabel is a lowkey yet seriously designed fintech product for the creative industries. It’s easier to split profits when a website supported by one of the world’s most powerful digital payment platforms, Stripe, guides us through the process of doing so.

Metalabel has shapeshifted conceptually during its short history, presenting itself not only as a sales and distribution platform, but also as a publishing initiative and a sort of thinktank promulgating coinages such as “groupcore,” defined as “software, tools, economics, and ideas that help people cooperate.” While A-Corps is conceived in the same spirit, it is not a product, or a means of distributing products, at least not at this juncture.

To designate A-Corps as a new institutional structure would be an overstatement—it’s one in a world of Strickler’s ideas—but it is clearly inspired by examples of what is known to art history as institutional critique, the artist-led movement that emerged in the late 1960s to interrogate the structural operations of the art world.

Like many of his age and cohort, Strickler is a prodigious user of LinkedIn, and the business networking platform was an amusing place to encounter a post about The Artist’s Reserved Rights Transfer and Sale Agreement, a 1971 contract developed by conceptual artist and dealer Seth Siegelaub and lawyer Robert Projansky to define and grant artists a set of rights when selling their work. Strickler has framed this document—one of many similarly critical interventions by Siegelaub—as a sort of Magna Carta for A-Corps.

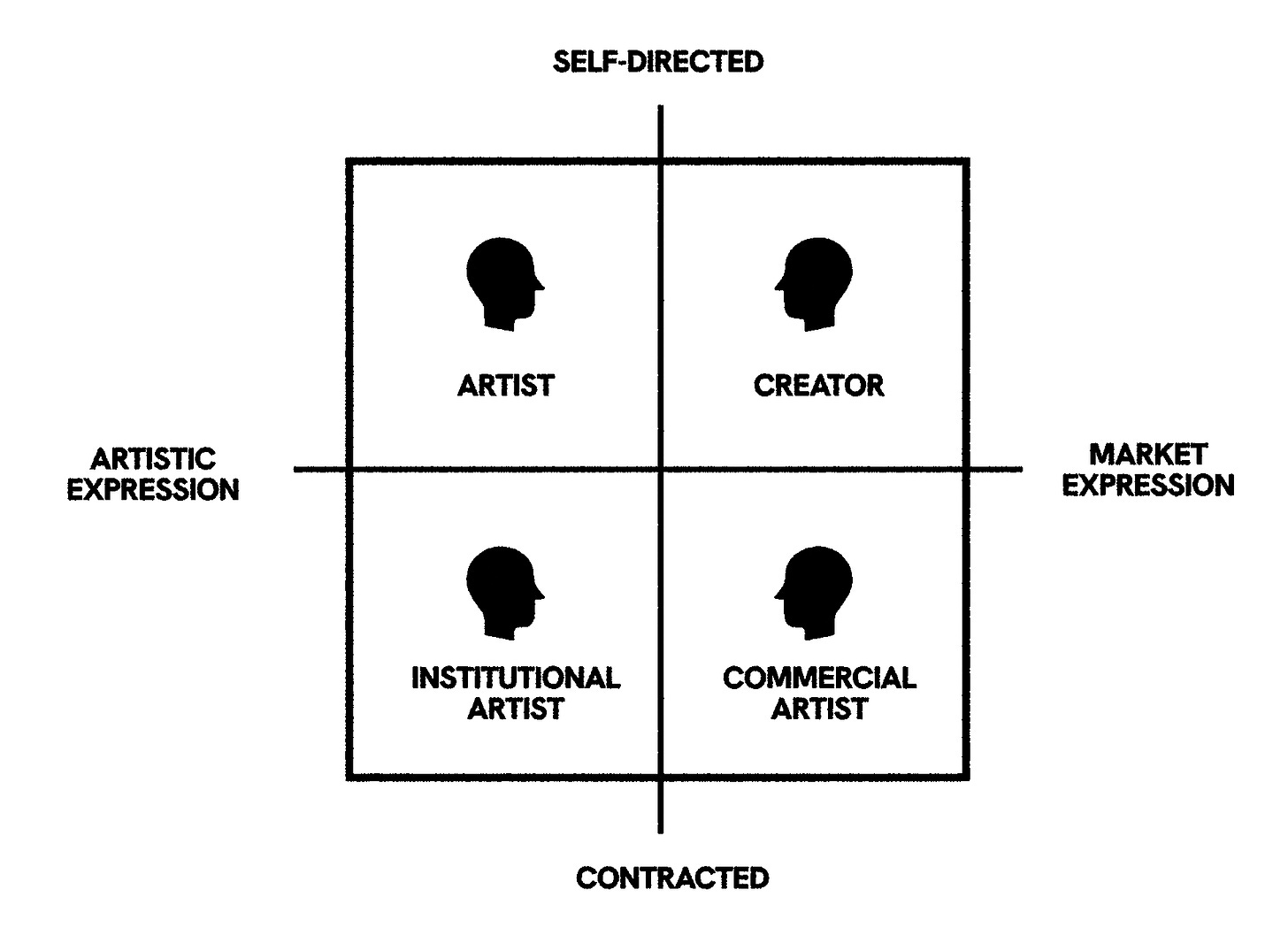

What Kickstarter, and now, Metalabel and A-Corps have in common is a desire to codify structural economic and social change in the arts, ensuring that people are simply and fairly paid. What does that look like, however, in today’s economy, compared to the situation more than fifteen years ago? Kickstarter helped introduce the concept of the “creator,” a much looser, more populist definition that pulled the classically defined “artist” away from the white cube gallery and onto a newly monetized internet. A-Corps seems to align with capital-A artists, which he took pains to define in relation to creators in another LinkedIn post.

As a practically minded spin-off of institutional critique, A-Corps brings to mind a very different yet also inspiring initiative that emerged concurrently with Kickstarter at another terrible moment for the arts: the wake of the 2008 financial crisis. Working Artists in the Greater Economy—better known as W.A.G.E.—was founded as a grassroots effort in New York. W.A.G.E.’s seemingly simple goal of establishing standards for artists’ fees in the nonprofit sector had been difficult to implement. Yet, by 2014, W.A.G.E. Certification allowed institutions to publicly commit to paying artists wages that meet W.A.G.E. standards. According to the organization’s current website, 146 institutions have been certified across the U.S. and more than $23 million has been paid out to artists through the program’s administration. Any organization can use W.A.G.E.’s fee calculator to help plan their operations—and hearteningly, all these years later, many still do.

W.A.G.E. effectively works with and within organizational structures—another classic hallmark of institutional critique. The difference of A-Corps is that it proposes collective organization outside of the institution. It makes sense that we’re seeing new systemic approaches in this trying moment. The institution itself, however, has its own structural logic. How then, will A-Corps gain traction?

Strickler is steeped in the ways and means of startup life, where concepts like fractional ownership are baked into the culture. Artists, however—especially those classically trained in American art schools—tend to lack formal financial education. As any accountant with clients in the arts can tell you, artists tend to focus on making, not business management, however shortsighted that may be.

Strickler’s challenge, then, is to somehow reach artists—not necessarily LinkedIn users—and provide the sort of simplified financial education that will inspire without overwhelming, and encourage artists to self-organize for the sake of their own financial benefit. This is an enormous hurdle, but Strickler is already jumping it with the Dark Forest Collective, which is producing some of the most accessible, bleeding-edge thinking out there about the culture and economies of the internet. Through its collective publishing work, the group has earned hundreds of thousands of dollars in sales; Strickler detailed the finances on Metalabel’s Substack. Selling books, in this case, is its own form of economic education—and Strickler’s transparency with the numbers echoes W.A.G.E.’s ongoing attempt to influence institutions. This openness might be the Dark Forest Collective’s most interesting and impactful work yet.

Sarah Hromack is the founder of Soft Labor, a consultancy that works with organizations, designers, and the culture industry. She is the author of the newsletter Soft Labor.